The evolution of community bank risk management

New system is about identifying, assessing, mitigating, measuring, monitoring and communicating risk

By Michael Berman

Once upon a time, risk management could be summed up with two words: credit risk.

With limited technology, basic services, compact operations and few, if any, critical third-party vendors, credit risk was the biggest concern a financial institution faced. The chief financial officer, controller or bank president was the de facto risk control officer.

Today, community banks take a much broader view of risk, including operational, transaction, reputation, compliance, strategic, cyber, third party and concentration risk. This multifaceted approach to risk touches every aspect of a financial institution. Everyone in the bank is a risk manager.

When an institution carefully assesses risk, it understands where it has advantages over the competition that it can exploit, which can include more market knowledge, greater flexibility, superior technology or a more efficient compliance management system. It also knows where there are weaknesses that need to be mitigated.

Addressing risk management at an enterprise level should create a more effective and efficient financial institution, but how can community banks get there?

Born of a scandal

While community banking risk management eventually expanded to include interest rate risk, community banks were slow to adapt other aspects of risk management. During the 1990s, risk management became a more common topic of discussion in business circles but it wasn’t widely embraced by community banking. Community banks addressed areas like disaster recovery, but it wasn’t necessarily viewed through today’s risk management lens.

That began to change with the failure of Enron and other corporate bankruptcies like Tyco International and WorldCom in the early 2000s. Energy company Enron was one of the 10 largest companies in the U.S., with more than $60 billion in assets, when it collapsed and declared bankruptcy in December 2001. Enron investors saw share prices plummet from $90 in August 2000 to less than 10 cents just over a year later, causing investors to lose an estimated $11 billion.

When most people think of these scandals, they think of fraud, but fraud doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It occurs when opportunity meets motive. In these cases of corporate scandal, abysmal to non-existent risk management was a leading factor in creating that opportunity.

At Enron, the company hid billions in losses by creating partnerships with companies that it owned and had financial conflicts of interest with auditor Arthur Anderson. Prior to the Enron scandal, Arthur Anderson was one of the most prestigious accounting firms in the world and a member of the Big Five. In the aftermath of the Enron scandal, the firm collapsed.

The lack of risk management and oversight extended into the board room at Enron because the board was not taking their responsibilities seriously. While the board defended itself by pointing out that Enron’s management had hidden many of its questionable and fraudulent practices from the board, a Senate permanent subcommittee investigation found there were “more than a dozen red flags” that were ignored.

The committee said the board enabled the company’s collapse “by allowing Enron to engage in high risk accounting, inappropriate conflict of interest transactions, extensive undisclosed off-the-books activities and excessive executive compensation. The board witnessed numerous indications of questionable practices by Enron management over several years but chose to ignore them to the detriment of Enron shareholders, employees and business associates.”

What kind of risk-taking went on at Enron? Risk didn’t even enter into the equation.

“Deals, especially in the finance division, were done at a rapid pace without much regard to whether they aligned with the strategic goals of the company or whether they complied with the company’s risk management policies,” reported the Journal of Accountancy in 2002. “As one knowledgeable Enron employee put it: ‘Good deal vs. bad deal? Didn’t matter. If it had a positive net present value (NPV) it could get done. Sometimes positive NPV didn’t even matter in the name of strategic significance.’”

Most bankers look back on these scandals and think about how they brought about The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which resulted in increased regulatory burden in the form of internal controls and attestations. But it also brought heightened attention to risk management and the need to assess, identify and mitigate risks across the organization.

A new risk management framework

One of the leading voices was The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), which provides thought leadership on internal controls and enterprise risk management (ERM) to improve performance and governance and reduce fraud.

One of the leading voices was The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), which provides thought leadership on internal controls and enterprise risk management (ERM) to improve performance and governance and reduce fraud.

In 1992, COSO published the Internal Control — Integrated Framework, which offered companies of all sizes a new way of looking at internal controls by shifting responsibility for these functions to the entire organization including the board and senior management. This framework would eliminate silos and add transparency and greater oversight. (This framework has been continually updated and embraced by financial regulators.)

The scandals of the early 2000s made it obvious COSO needed to provide guidance that went beyond operations, financial reporting and compliance. In 2004, COSO published Enterprise Risk Management — Integrated Framework. The framework introduced risk management principles like risk tolerance and risk appetite and explained risk management principles.

Over the next few years, many community banks began to consider risk management but were slow to adopt an enterprise-wide approach to risk management. What’s the difference? Risk management uses a rifle approach, shooting one thing at a time. It’s the risk management equivalent of the carnival game whack-a- mole. A problem pops up, you knock it out and move on to the next one.

ERM, on the other hand, is a system to manage risk. It examines risk holistically to understand how different areas of the institution interconnect. It’s about identifying, assessing, mitigating, measuring, monitoring and communicating risk. The goal of ERM isn’t just to identify risks to exploit or reduce them. It’s also to create value.

Crisis strikes and ERM grows

In the aftermath of the financial crisis in 2008, regulators were looking for systems to help better mitigate risk. The financial crisis stemmed from a failure of risk management, one where the board and management at the largest financial institutions were not appreciating the potential risks in their mortgage portfolios in a quest for ever-increasing profits.

These control failures combined with increased cyber vulnerabilities and reliance on third-party service providers created an environment where regulators began to take a closer look at various types of risks, especially in the vendor management, compliance management and business continuity arenas.

Updated guidance on risk areas like third-party vendors, compliance management systems and business continuity efforts made community bankers increasingly aware of the overlap between different areas of risk management. Risk management can no longer be thought of as stand-alone elements of the bank’s operational risk management program, because they are intertwined.

In 2016, COSO released an update to its voluntary framework with best practices for ERM, “Enterprise Risk Management — Integrating with Strategy and Performance.” Compared to the previous version, today’s COSO framework does much more to integrate risk into the strategic planning process.

The framework “positions risk in the context of an organization’s performance, rather than as the subject of an isolated exercise” and “enables organizations to better anticipate risk so they can get ahead of it, with an understanding that change creates opportunities, not simply the potential for crises.”

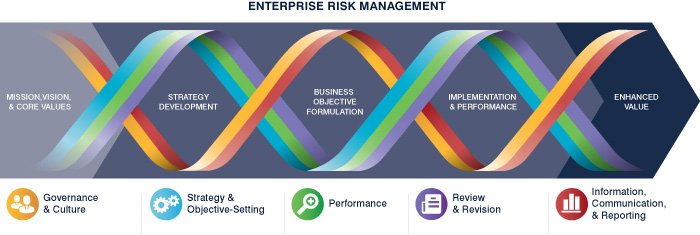

The COSO framework divides the components and principles of an effective ERM into five categories:

- Governance & culture

- Strategy & objective-setting

- Performance

- Review & revision

- Information, communication and reporting

COSO’s approach emphasizes how these five components are banded together in ribbons that wrap around the key steps of developing and executing a business strategy:

- Mission, vision and core values

- Strategy development

- Business objective formulation

- Implementation and performance

- Enhanced value

It’s no accident that the design resembles the double helix structure of DNA. It’s a nod to the idea that ERM needs to be hard-wired and ingrained into an institution’s structure. It’s not an add-on but fundamental to the organization’s existence. Take one component away and the whole structure unravels.

The risk management-strategy connection

Today more and more community banks are making the connection between risk management and strategy, and they are embracing ERM best practices and tools. They are balancing effective governance and strategic planning with risk management to ensure they enter into new businesses, products and systems with its eyes wide open.

The structure of community bank ERM programs varies but the basic principles do not. From sophisticated banks with chief risk officers, fully staffed risk departments and risk committees to smaller banks where CEOs and other key employees juggle risk management duties, community banks are implementing ERM and increasing the resources dedicated to it. They are making progress in eliminating the silos that hinder collaboration and a clear view of risk.

In return, ERM is helping community banks develop and execute strategies to mitigate potential risks and help the board and management decide where to spend limited economic and human capital resources.

Going forward, eliminating silos will become increasingly critical. Community banks’ changing and increasingly complex operating environment has elevated operational risk, as the OCC has noted in its past few issues of its Semiannual Risk Perspective. Strategic risk also requires additional attention, particularly when it comes to compliance and cybersecurity.

Community banks with strong, ongoing enterprise risk management programs will be the ones best able to adapt and evolve in a changing environment.

Michael Berman is the founder and CEO of Ncontracts, a leading provider of risk management solutions. His extensive background in legal and regulatory matters has afforded him unique insights into solving operational risk management challenges and drives Ncontracts’ mission to efficiently and effectively manage operational risk. During his legal career, Berman was involved in numerous regulatory, compliance and contract management challenges and assisted in the development of information systems to better manage these efforts. www.ncontracts.com